Calculators, Power Series and Chebyshev Polynomials: Unterschied zwischen den Versionen

(→Conclusion: The Point of the Story) |

(→Approximation by Chebyshev Polynomials) |

||

| (31 dazwischenliegende Versionen von einem Benutzer werden nicht angezeigt) | |||

| Zeile 1: | Zeile 1: | ||

| − | Originating author: | + | Originating author: Graeme Cohen |

| + | Of all the familiar functions, such as trigonometric, exponential and logarithmic functions, surely the simplest to evaluate are | ||

| + | polynomial functions. The purposes of this article are, first, to introduce the concept of a power series, which can be thought | ||

| + | of as a polynomial function of infinite degree, and, second, to show their application to evaluating functions on a calculator. | ||

| + | When a calculator gives values of trigonometric or exponential or logarithmic functions, the most straightforward way is to | ||

| + | evaluate polynomial functions obtained by truncating power series that represent those functions and are sufficiently good | ||

| + | approximations. But there are often better ways. We will, in particular, deduce a power series for <math>\,\sin\,x</math> and | ||

| + | will see how to improve on the straightforward approach to approximating its values. That will involve | ||

| + | [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chebyshev_polynomials Chebyshev polynomials], which are used in many ways for a similar purpose and | ||

| + | in many other applications, as well. (For trigonometric functions, the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cordic Cordic] algorithm is | ||

| + | in fact often the preferred method of evaluation---the subject of another article here, perhaps.) | ||

| − | + | In the spirit of Felix Klein, there will be some reliance on a graphical approach. Other than that, we need only some basic | |

| − | + | trigonometry and calculus. | |

| − | |||

== Manipulations with geometric series == | == Manipulations with geometric series == | ||

| − | |||

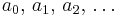

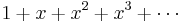

| − | <math> | + | The ''geometric series'' <math>1+x+x^2+x^3+\cdots</math> is the simplest power series. The sum of the series exists when |

| − | 1+x+x^2+x^3+\cdots=\frac 1{1-x}, \quad \mathrm{when}\ |x|<1. \qquad\qquad (1) | + | <math>|x|<1\,</math>. In fact, |

| − | </math> | + | |

| + | <math> 1+x+x^2+x^3+\cdots=\frac 1{1-x}, \quad \mathrm{when}\ |x|<1. \qquad\qquad (1) </math> | ||

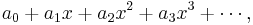

The general form of a ''power series'' is | The general form of a ''power series'' is | ||

| − | <math> | + | <math> a_0+a_1x+a_2x^2+a_3x^3+\cdots, </math> |

| − | a_0+a_1x+a_2x^2+a_3x^3+\cdots, | + | |

| − | </math> | + | |

| − | so the geometric series above is a power series in which all the coefficients <math>a_0,\,a_1,\,a_2,\,\ldots</math> are equal to 1. In | + | so the geometric series above is a power series in which all the coefficients <math>a_0,\,a_1,\,a_2,\,\ldots</math> are equal to |

| − | this case, since the series converges to <math>1/(1-x)\,</math> when <math>|x|<1\,</math>, we say that the function <math>f\,</math>, where | + | 1. In this case, since the series converges to <math>1/(1-x)\,</math> when <math>|x|<1\,</math>, we say that the function |

| + | <math>f\,</math>, where | ||

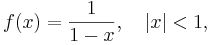

| − | <math> | + | <math> f(x)=\frac1{1-x}, \quad |x|<1, </math> |

| − | f(x)=\frac1{1-x}, \quad |x|<1, | + | |

| − | </math> | + | |

| − | has the ''series expansion'' <math>1+x+x^2+x^3+\cdots</math>, or that <math>f\,</math> is represented by this series. We are interested initially to show some | + | has the ''series expansion'' <math>1+x+x^2+x^3+\cdots</math>, or that <math>f\,</math> is represented by this series. We are |

| − | other functions that can be represented by power series. | + | interested initially to show some other functions that can be represented by power series. |

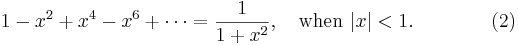

| − | Many such functions may be obtained directly from the result in (1). For example, by replacing <math>x\,</math> by <math>-x^2\,</math>, we immediately have a | + | Many such functions may be obtained directly from the result in (1). For example, by replacing <math>x\,</math> by |

| − | series representation for the function <math>1/(1+x^2)\,</math>: | + | <math>-x^2\,</math>, we immediately have a series representation for the function <math>1/(1+x^2)\,</math>: |

| − | <math> | + | <math> 1-x^2+x^4-x^6+\cdots=\frac 1{1+x^2}, \quad \mathrm{when}\ |x|<1. \qquad\qquad (2) </math> |

| − | 1-x^2+x^4-x^6+\cdots=\frac 1{1+x^2}, \quad \mathrm{when}\ |x|<1. \qquad\qquad (2) | + | |

| − | </math> | + | |

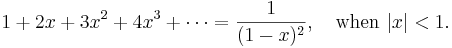

We can differentiate both sides of (1) to give a series representation of the function <math>1/(1-x)^2\,</math>: | We can differentiate both sides of (1) to give a series representation of the function <math>1/(1-x)^2\,</math>: | ||

| − | <math> | + | <math> 1+2x+3x^2+4x^3+\cdots=\frac 1{(1-x)^2}, \quad \mathrm{when}\ |x|<1. </math> |

| − | 1+2x+3x^2+4x^3+\cdots=\frac 1{(1-x)^2}, \quad \mathrm{when}\ |x|<1. | + | |

| − | </math> | + | |

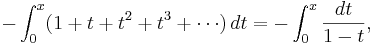

| − | We can also integrate both sides of (1). Multiply through by <math>-1</math> (for convenience), then write <math>t\,</math> for <math>x\,</math> and integrate with respect | + | We can also integrate both sides of (1). Multiply through by <math>-1</math> (for convenience), then write <math>t\,</math> for |

| − | to <math>t\,</math> from 0 to <math>x\,</math>, where <math>|x|<1\,</math>: | + | <math>x\,</math> and integrate with respect to <math>t\,</math> from 0 to <math>x\,</math>, where <math>|x|<1\,</math>: |

| − | <math> | + | <math> -\int_0^x (1+t+t^2+t^3+\cdots)\,dt=-\int_0^x\frac {dt}{1-t}, </math> |

| − | -\int_0^x (1+t+t^2+t^3+\cdots)\,dt=-\int_0^x\frac {dt}{1-t}, | + | |

| − | </math> | + | |

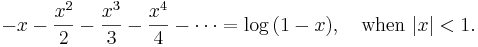

so | so | ||

| − | <math> | + | <math> -x-\frac{x^2}2-\frac{x^3}3-\frac{x^4}4-\cdots=\log\,(1-x), \quad \mathrm{when}\ |x|<1. </math> |

| − | -x-\frac{x^2}2-\frac{x^3}3-\frac{x^4}4-\cdots=\log\,(1-x), \quad \mathrm{when}\ |x|<1. | + | |

| − | </math> | + | |

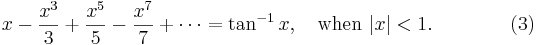

| − | So this gives a series representation of the function <math>\log\,(1-x)</math> for <math>|x|<1\,</math>. In the same way, from (2), | + | So this gives a series representation of the function <math>\log\,(1-x)</math> for <math>|x|<1\,</math>. In the same way, from |

| + | (2), | ||

| − | <math> | + | <math> x-\frac{x^3}3+\frac{x^5}5-\frac{x^7}7+\cdots=\tan^{-1}x, \quad \mathrm{when}\ |x|<1. \qquad\qquad (3) </math> |

| − | x-\frac{x^3}3+\frac{x^5}5-\frac{x^7}7+\cdots=\tan^{-1}x, \quad \mathrm{when}\ |x|<1. \qquad\qquad (3) | + | |

| − | </math> | + | |

Much of what we have done here (and will do later) requires justification, but we can leave that to the textbooks. | Much of what we have done here (and will do later) requires justification, but we can leave that to the textbooks. | ||

| Zeile 68: | Zeile 65: | ||

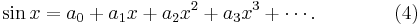

We will show next how to find a power series representation for <math>\sin\,x</math>. In general terms, we can write | We will show next how to find a power series representation for <math>\sin\,x</math>. In general terms, we can write | ||

| − | <math> | + | <math> \sin x=a_0+a_1x+a_2x^2+a_3x^3+\cdots. \qquad\qquad (4) </math> |

| − | \sin x=a_0+a_1x+a_2x^2+a_3x^3+\cdots. \qquad\qquad (4) | + | |

| − | </math> | + | |

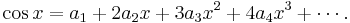

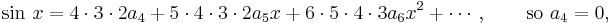

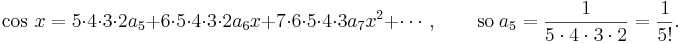

Put <math>x=0\,</math>, and immediately we have <math>a_0=0\,</math>. Differentiate both sides of (4): | Put <math>x=0\,</math>, and immediately we have <math>a_0=0\,</math>. Differentiate both sides of (4): | ||

| − | <math> | + | <math> \cos x=a_1+2a_2x+3a_3x^2+4a_4x^3+\cdots. </math> |

| − | \cos x=a_1+2a_2x+3a_3x^2+4a_4x^3+\cdots. | + | |

| − | </math> | + | |

Again put <math>x=0\,</math>, giving <math>a_1=1\,</math>. Keep differentiating and putting <math>x=0\,</math>: | Again put <math>x=0\,</math>, giving <math>a_1=1\,</math>. Keep differentiating and putting <math>x=0\,</math>: | ||

| − | <math> | + | <math> -\sin\,x = 2a_2+3\cdot2a_3x+4\cdot3a_4x^2+5\cdot4a_5x^3+\cdots, \qquad\mathrm{so}\ a_2=0, </math> |

| − | -\sin\,x = 2a_2+3\cdot2a_3x+4\cdot3a_4x^2+5\cdot4a_5x^3+\cdots, \qquad\mathrm{so}\ a_2=0, | + | |

| − | </math> | + | |

<math> | <math> | ||

| Zeile 95: | Zeile 86: | ||

\cos\,x = 5\cdot4\cdot3\cdot2a_5+6\cdot5\cdot4\cdot3\cdot2a_6x+7\cdot6\cdot5\cdot4\cdot3a_7x^2+\cdots, \qquad\mathrm{so}\ a_5=\frac1{5\cdot4\cdot3\cdot2}=\frac1{5!}. | \cos\,x = 5\cdot4\cdot3\cdot2a_5+6\cdot5\cdot4\cdot3\cdot2a_6x+7\cdot6\cdot5\cdot4\cdot3a_7x^2+\cdots, \qquad\mathrm{so}\ a_5=\frac1{5\cdot4\cdot3\cdot2}=\frac1{5!}. | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

| + | |||

In this way, we can find a formula for all the coefficients <math>a_0,\,a_1,\,a_2,\,\ldots</math>, namely, | In this way, we can find a formula for all the coefficients <math>a_0,\,a_1,\,a_2,\,\ldots</math>, namely, | ||

| − | <math> | + | <math> a_{2n}=0, \qquad\qquad a_{2n+1}=\frac{(-1)^n}{(2n+1)!}, </math> |

| − | a_{2n}=0, \qquad\qquad a_{2n+1}=\frac{(-1)^n}{(2n+1)!}, | + | |

| − | </math> | + | |

for <math>n=0,\,1,\,2,\,\ldots</math>. (The coefficients of even index and those of odd index are specified separately.) Thus | for <math>n=0,\,1,\,2,\,\ldots</math>. (The coefficients of even index and those of odd index are specified separately.) Thus | ||

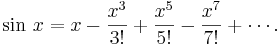

| − | <math> | + | <math> \sin\,x=x-\frac{x^3}{3!}+\frac{x^5}{5!}-\frac{x^7}{7!}+\cdots. </math> |

| − | \sin\,x=x-\frac{x^3}{3!}+\frac{x^5}{5!}-\frac{x^7}{7!}+\cdots. | + | |

| − | </math> | + | |

| − | This is the power series representation that we were after. From the way we developed it, it is reasonable that the series will | + | This is the power series representation that we were after. From the way we developed it, it is reasonable that the series will |

| − | <math>\,\sin\,x</math> for values of <math>x\,</math> at and near 0 (say for <math>|x|<1\,</math>, as for all the earlier examples), so it is surprising to know that it can | + | represent <math>\,\sin\,x</math> for values of <math>x\,</math> at and near 0 (say for <math>|x|<1\,</math>, as for all the |

| − | be shown that the series represents <math>\sin\,x</math> for ''all'' values of <math>x\,</math>. Then partial sums of the series, obtained by stopping after | + | earlier examples), so it is surprising to know that it can be shown that the series represents <math>\sin\,x</math> for ''all'' |

| − | some finite number of terms, should give polynomial functions that can be used to find approximate values of the sine function, such as | + | values of <math>x\,</math>. Then partial sums of the series, obtained by stopping after some finite number of terms, should give |

| − | you find in tables of trigonometric functions or as output on a calculator. | + | polynomial functions that can be used to find approximate values of the sine function, such as you find in tables of |

| + | trigonometric functions or as output on a calculator. | ||

==Approximation by Chebyshev Polynomials== | ==Approximation by Chebyshev Polynomials== | ||

| Zeile 118: | Zeile 107: | ||

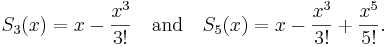

For example, write | For example, write | ||

| − | <math> | + | <math> S_3(x)=x-\frac{x^3}{3!} \quad \mathrm{and} \quad S_5(x)=x-\frac{x^3}{3!}+\frac{x^5}{5!}. </math> |

| − | S_3(x)=x-\frac{x^3}{3!} \quad \mathrm{and} \quad S_5(x)=x-\frac{x^3}{3!}+\frac{x^5}{5!}. | + | |

| − | </math> | + | |

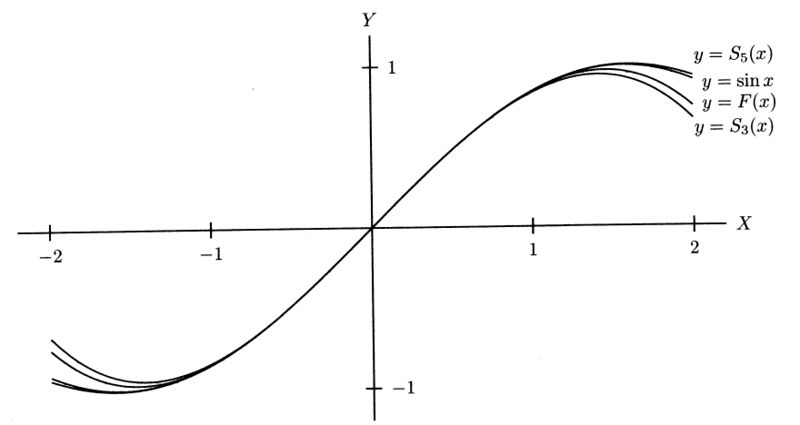

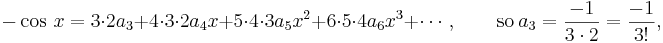

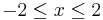

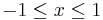

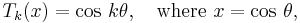

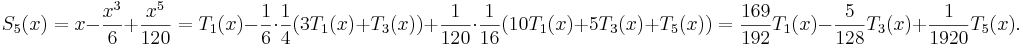

| − | The cubic polynomial <math>S_3(x)\,</math> and the quintic polynomial <math>S_5(x)\,</math> are plotted below, along with <math>\,\sin\,x</math>, all for <math>-2\le x\le 2</math>. It can be seen that these are both very good approximations for <math>-1\le x\le1</math>, say, but not so good near <math>x=\pm2</math>. The quintic | + | The cubic polynomial <math>S_3(x)\,</math> and the quintic polynomial <math>S_5(x)\,</math> are plotted below, along with |

| − | <math>S_5\,</math> is much better than the cubic <math>S_3\,</math> in these outer regions, as might be expected, but can we do better than <math>S_3\,</math> with some other cubic polynomial function? | + | <math>\,\sin\,x</math>, all for <math>-2\le x\le 2</math>. It can be seen that these are both very good approximations for |

| + | <math>-1\le x\le1</math>, say, but not so good near <math>x=\pm2</math>. The quintic <math>S_5\,</math> is much better than the | ||

| + | cubic <math>S_3\,</math> in these outer regions, as might be expected, but can we do better than <math>S_3\,</math> with some | ||

| + | other cubic polynomial function? | ||

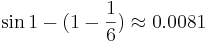

| − | When <math>x=1\,</math>, for example, the error in using the cubic is <math>\sin1-(1-\frac16)\approx0.0081</math>. We will construct a cubic polynomial function <math>F\,</math> whose values differ from those of <math>\,\sin\,x</math> by less than 0.001 for <math>|x|\le1</math>. The curve <math>y=F(x)\,</math> has been included in the graph below for <math>|x|\le2</math>, and it is clear from the graph that this curve is closer to that of <math>y=\sin\,x</math> than <math>y=S_3(x)\,</math> is, even near <math>x=\pm2</math>. | + | When <math>x=1\,</math>, for example, the error in using the cubic is <math>\sin1-(1-\frac16)\approx0.0081</math>. We will |

| + | construct a cubic polynomial function <math>F\,</math> whose values differ from those of <math>\,\sin\,x</math> by less than | ||

| + | 0.001 for <math>|x|\le1</math>. The curve <math>y=F(x)\,</math> has been included in the graph below for <math>|x|\le2</math>, | ||

| + | and it is clear from the graph that this curve is closer to that of <math>y=\sin\,x</math> than <math>y=S_3(x)\,</math> is, even | ||

| + | near <math>x=\pm2</math>. | ||

[[Bild:Chebysev fig.jpg | 800px]] | [[Bild:Chebysev fig.jpg | 800px]] | ||

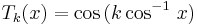

| − | We will use ''Chebyshev polynomials'' to construct <math>F\,</math>. These are used extensively in approximation problems, as we are doing here. They are the functions <math>T_k\,</math> given by | + | We will use ''Chebyshev polynomials'' to construct <math>F\,</math>. These are used extensively in approximation problems, as we |

| + | are doing here. They are the functions <math>T_k\,</math> given by | ||

| − | <math> | + | <math> T_k(x)=\cos\,k\theta, \quad\mathrm{where}\ x=\cos\,\theta, </math> |

| − | T_k(x)=\cos\,k\theta, \quad\mathrm{where}\ x=\cos\,\theta, | + | |

| − | </math> | + | |

| − | for integer <math>k\ge0</math> (or you can write <math>T_k(x)=\cos\,(k\cos^{-1}\,x)</math>). By properties of the cosine, they all have domain <math>[-1,1]\,</math> and their range is also in <math>[-1,1]\,</math>. Putting <math>k=0\,</math> and <math>k=1\,</math> gives | + | for integer <math>k\ge0</math> (or you can write <math>T_k(x)=\cos\,(k\cos^{-1}\,x)</math>). By properties of the cosine, they |

| + | all have domain <math>[-1,1]\,</math> and their range is also in <math>[-1,1]\,</math>. Putting <math>k=0\,</math> and | ||

| + | <math>k=1\,</math> gives | ||

| − | <math> | + | <math> T_0(x)=1, \qquad T_1(x)=x, </math> |

| − | T_0(x)=1, \qquad T_1(x)=x, | + | |

| − | </math> | + | |

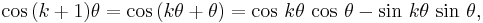

| − | but it is not immediately apparent that the <math>T_k\,</math> are indeed polynomials for <math>k\ge2</math>. To see that this is the case, recall that | + | but it is not immediately apparent that the <math>T_k\,</math> are indeed polynomials for <math>k\ge2</math>. To see that this is |

| + | the case, recall that | ||

| − | <math> | + | <math> \cos\,(k+1)\theta=\cos\,(k\theta+\theta)=\cos\,k\theta\,\cos\,\theta-\sin\,k\theta\,\sin\,\theta, </math> |

| − | \cos\,(k+1)\theta=\cos\,(k\theta+\theta)=\cos\,k\theta\,\cos\,\theta-\sin\,k\theta\,\sin\,\theta, | + | |

| − | </math> | + | |

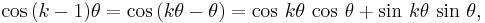

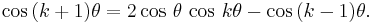

| − | <math> | + | <math> \cos\,(k-1)\theta=\cos\,(k\theta-\theta)=\cos\,k\theta\,\cos\,\theta+\sin\,k\theta\,\sin\,\theta, </math> |

| − | \cos\,(k-1)\theta=\cos\,(k\theta-\theta)=\cos\,k\theta\,\cos\,\theta+\sin\,k\theta\,\sin\,\theta, | + | |

| − | </math> | + | |

from which, after adding these, | from which, after adding these, | ||

| − | <math> | + | <math> \cos\,(k+1)\theta=2\cos\,\theta\,\cos\,k\theta-\cos\,(k-1)\theta. </math> |

| − | \cos\,(k+1)\theta=2\cos\,\theta\,\cos\,k\theta-\cos\,(k-1)\theta. | + | |

| − | </math> | + | |

Therefore, | Therefore, | ||

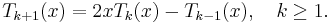

| − | <math> | + | <math> T_{k+1}(x)=2xT_k(x)-T_{k-1}(x), \quad k\ge1. </math> |

| − | T_{k+1}(x)=2xT_k(x)-T_{k-1}(x), \quad k\ge1. | + | |

| − | </math> | + | |

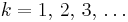

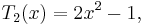

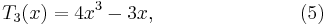

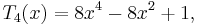

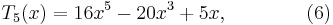

Now put <math>k=1,\,2,\,3,\,\ldots</math> and obtain | Now put <math>k=1,\,2,\,3,\,\ldots</math> and obtain | ||

| − | <math> | + | <math> T_2(x) = 2x^2-1, \quad </math> |

| − | T_2(x) = 2x^2-1, \quad | + | |

| − | </math> | + | |

| − | <math> | + | <math> T_3(x) = 4x^3-3x, \qquad\qquad\qquad\quad\ (5) </math> |

| − | T_3(x) = 4x^3-3x, \qquad\qquad\qquad\quad\ (5) | + | |

| − | </math> | + | |

| − | <math> | + | <math> T_4(x) = 8x^4-8x^2+1, \quad </math> |

| − | T_4(x) = 8x^4-8x^2+1, \quad | + | |

| − | </math> | + | |

| − | <math> | + | <math> T_5(x) = 16x^5-20x^3+5x, \qquad\qquad (6) </math> |

| − | T_5(x) = 16x^5-20x^3+5x, \qquad\qquad (6) | + | |

| − | </math> | + | |

| − | and so on, clearly obtaining a polynomial each time. As polynomials, we no longer need to think of their domains as restricted to <math>[-1,1]\,</math>. | + | and so on, clearly obtaining a polynomial each time. As polynomials, we no longer need to think of their domains as restricted to |

| + | <math>[-1,1]\,</math>. | ||

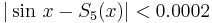

| − | Returning to our problem of approximating <math>\,\sin\,x</math> for <math>|x|\le1</math> with error less than 0.001, we notice first that the quintic | + | Returning to our problem of approximating <math>\,\sin\,x</math> for <math>|x|\le1</math> with error less than 0.001, we notice |

| − | <math>S_5\,</math> has that property. In fact, | + | first that the quintic <math>S_5\,</math> has that property. In fact, |

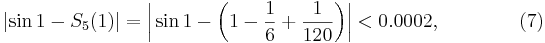

| − | <math> | + | <math> \left|\sin1-S_5(1)\right|=\left|\,\sin1-\left(1-\frac16+\frac1{120}\right)\right| |

| − | \left|\sin1-S_5(1)\right|=\left|\,\sin1-\left(1-\frac16+\frac1{120}\right)\right| | + | |

<0.0002, \qquad\qquad (7) | <0.0002, \qquad\qquad (7) | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

| − | and the theory of alternating infinite series shows that <math>|\sin\,x-S_5(x)|<0.0002</math> throughout our interval, as certainly seems | + | and the theory of alternating infinite series shows that <math>|\sin\,x-S_5(x)|<0.0002</math> throughout our interval, as |

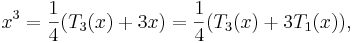

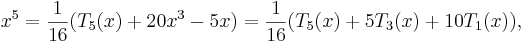

| − | reasonable from the figure. We next express <math>S_5(x)\,</math> in terms of Chebyshev polynomials. Using (5) and (6), we have | + | certainly seems reasonable from the figure. We next express <math>S_5(x)\,</math> in terms of Chebyshev polynomials. Using (5) |

| + | and (6), we have | ||

| − | <math> | + | <math> x=T_1(x), \quad </math> |

| − | x=T_1(x), \quad | + | |

| − | </math> | + | |

| − | <math> | + | <math> x^3=\frac14(T_3(x)+3x)=\frac14(T_3(x)+3T_1(x)), </math> |

| − | x^3=\frac14(T_3(x)+3x)=\frac14(T_3(x)+3T_1(x)), | + | |

| − | </math> | + | |

| − | <math> | + | <math> x^5=\frac1{16}(T_5(x)+20x^3-5x)=\frac1{16}(T_5(x)+5T_3(x)+10T_1(x)), </math> |

| − | x^5=\frac1{16}(T_5(x)+20x^3-5x)=\frac1{16}(T_5(x)+5T_3(x)+10T_1(x)), | + | |

| − | </math> | + | |

so | so | ||

| − | <math> | + | <math> S_5(x)=x-\frac{x^3}{6}+\frac{x^5}{120} |

| − | S_5(x)=x-\frac{x^3}{6}+\frac{x^5}{120} =T_1(x)-\frac16\cdot\frac14(3T_1(x)+T_3(x))+\frac1{120}\cdot\frac1{16}(10T_1(x)+5T_3(x)+T_5(x)) =\frac{169}{192}T_1(x)-\frac5{128}T_3(x)+\frac1{1920}T_5(x). | + | =T_1(x)-\frac16\cdot\frac14(3T_1(x)+T_3(x))+\frac1{120}\cdot\frac1{16}(10T_1(x)+5T_3(x)+T_5(x)) |

| − | </math> | + | =\frac{169}{192}T_1(x)-\frac5{128}T_3(x)+\frac1{1920}T_5(x). </math> |

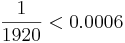

| − | Since <math>|T_5(x)|\le1</math> when <math>|x|\le1</math>, omitting the term <math>\frac1{1920}T_5(x)</math> will admit a further error of at most | + | Since <math>|T_5(x)|\le1</math> when <math>|x|\le1</math>, omitting the term <math>\frac1{1920}T_5(x)</math> will admit a further |

| − | <math>\frac1{1920}<0.0006</math> which, using (7), gives a total error less than 0.0008, still within our bound of 0.001. Now, | + | error of at most <math>\frac1{1920}<0.0006</math> which, using (7), gives a total error less than 0.0008, still within our bound |

| + | of 0.001. Now, | ||

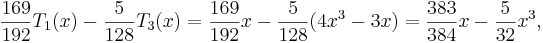

| − | <math> | + | <math> \frac{169}{192}T_1(x)-\frac5{128}T_3(x) |

| − | \frac{169}{192}T_1(x)-\frac5{128}T_3(x) | + | |

=\frac{169}{192}x-\frac5{128}(4x^3-3x)=\frac{383}{384}x-\frac5{32}x^3, | =\frac{169}{192}x-\frac5{128}(4x^3-3x)=\frac{383}{384}x-\frac5{32}x^3, | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

| Zeile 224: | Zeile 197: | ||

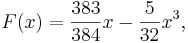

We have thus shown, partly through a graphical justification, that values of the cubic function <math>F\,</math>, where | We have thus shown, partly through a graphical justification, that values of the cubic function <math>F\,</math>, where | ||

| − | <math> | + | <math> F(x)=\frac{383}{384}x-\frac5{32}x^3, </math> |

| − | F(x)=\frac{383}{384}x-\frac5{32}x^3, | + | |

| − | </math> | + | |

| − | are closer to values of <math>\,\sin\,x</math>, for <math>|x|\le2</math>, than are values of the cubic function <math>x-\frac16x^3</math>, which is obtained from the power | + | are closer to values of <math>\,\sin\,x</math>, for <math>|x|\le2</math>, than are values of the cubic function |

| − | series representation of <math>\ \sin\,x</math>. | + | <math>x-\frac16x^3</math>, which is obtained from the power series representation of <math>\ \sin\,x</math>. |

==Conclusion: The Point of the Story== | ==Conclusion: The Point of the Story== | ||

| Zeile 236: | Zeile 207: | ||

The procedure outlined above is known as ''economization'' of power series and is studied in the branch of mathematics known as [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/numerical_analysis numerical analysis]. | The procedure outlined above is known as ''economization'' of power series and is studied in the branch of mathematics known as [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/numerical_analysis numerical analysis]. | ||

| − | Economization is not always necessary for evaluating the sine function. Because <math>\sin\,x</math> is approximately <math>x\,</math> when <math>x\,</math> is small, this is often good enough! See Chuck Allison, [http://uvu.freshsources.com/page1/page8/page16/files/sine.pdf Machine Computation of the Sine Function], for more on this. We mentioned at the beginning that the Cordic algorithm is often better still, but for evaluating other functions, particularly <math>\tan^{-1}\,x</math>, has the ''slowly converging'' power series expansion found in (3), economization is considered to be essential. | + | Economization is not always necessary for evaluating the sine function. Because <math>\sin\,x</math> is approximately <math>x\,</math> when <math>|x|\,</math> is small, this is often good enough! See Chuck Allison, [http://uvu.freshsources.com/page1/page8/page16/files/sine.pdf Machine Computation of the Sine Function], for more on this. We mentioned at the beginning that the Cordic algorithm is often better still, but for evaluating other functions on a calculator, particularly <math>\tan^{-1}\,x</math>, which has the ''slowly converging'' power series expansion found in (3), economization is considered to be essential. |

Perhaps the point of the story is that the obvious can very often be improved upon. | Perhaps the point of the story is that the obvious can very often be improved upon. | ||

Aktuelle Version vom 4. Juli 2010, 04:00 Uhr

Originating author: Graeme Cohen

Of all the familiar functions, such as trigonometric, exponential and logarithmic functions, surely the simplest to evaluate are

polynomial functions. The purposes of this article are, first, to introduce the concept of a power series, which can be thought

of as a polynomial function of infinite degree, and, second, to show their application to evaluating functions on a calculator.

When a calculator gives values of trigonometric or exponential or logarithmic functions, the most straightforward way is to

evaluate polynomial functions obtained by truncating power series that represent those functions and are sufficiently good

approximations. But there are often better ways. We will, in particular, deduce a power series for  and

will see how to improve on the straightforward approach to approximating its values. That will involve

Chebyshev polynomials, which are used in many ways for a similar purpose and

in many other applications, as well. (For trigonometric functions, the Cordic algorithm is

in fact often the preferred method of evaluation---the subject of another article here, perhaps.)

and

will see how to improve on the straightforward approach to approximating its values. That will involve

Chebyshev polynomials, which are used in many ways for a similar purpose and

in many other applications, as well. (For trigonometric functions, the Cordic algorithm is

in fact often the preferred method of evaluation---the subject of another article here, perhaps.)

In the spirit of Felix Klein, there will be some reliance on a graphical approach. Other than that, we need only some basic trigonometry and calculus.

Inhaltsverzeichnis |

Manipulations with geometric series

The geometric series  is the simplest power series. The sum of the series exists when

is the simplest power series. The sum of the series exists when

. In fact,

. In fact,

The general form of a power series is

so the geometric series above is a power series in which all the coefficients  are equal to

1. In this case, since the series converges to

are equal to

1. In this case, since the series converges to  when

when  , we say that the function

, we say that the function

, where

, where

has the series expansion  , or that

, or that  is represented by this series. We are

interested initially to show some other functions that can be represented by power series.

is represented by this series. We are

interested initially to show some other functions that can be represented by power series.

Many such functions may be obtained directly from the result in (1). For example, by replacing  by

by

, we immediately have a series representation for the function

, we immediately have a series representation for the function  :

:

We can differentiate both sides of (1) to give a series representation of the function  :

:

We can also integrate both sides of (1). Multiply through by  (for convenience), then write

(for convenience), then write  for

for

and integrate with respect to

and integrate with respect to  from 0 to

from 0 to  , where

, where  :

:

so

So this gives a series representation of the function  for

for  . In the same way, from

(2),

. In the same way, from

(2),

Much of what we have done here (and will do later) requires justification, but we can leave that to the textbooks.

The power series for the sine function

We will show next how to find a power series representation for  . In general terms, we can write

. In general terms, we can write

Put  , and immediately we have

, and immediately we have  . Differentiate both sides of (4):

. Differentiate both sides of (4):

Again put  , giving

, giving  . Keep differentiating and putting

. Keep differentiating and putting  :

:

In this way, we can find a formula for all the coefficients  , namely,

, namely,

for  . (The coefficients of even index and those of odd index are specified separately.) Thus

. (The coefficients of even index and those of odd index are specified separately.) Thus

This is the power series representation that we were after. From the way we developed it, it is reasonable that the series will

represent  for values of

for values of  at and near 0 (say for

at and near 0 (say for  , as for all the

earlier examples), so it is surprising to know that it can be shown that the series represents

, as for all the

earlier examples), so it is surprising to know that it can be shown that the series represents  for all

values of

for all

values of  . Then partial sums of the series, obtained by stopping after some finite number of terms, should give

polynomial functions that can be used to find approximate values of the sine function, such as you find in tables of

trigonometric functions or as output on a calculator.

. Then partial sums of the series, obtained by stopping after some finite number of terms, should give

polynomial functions that can be used to find approximate values of the sine function, such as you find in tables of

trigonometric functions or as output on a calculator.

Approximation by Chebyshev Polynomials

For example, write

The cubic polynomial  and the quintic polynomial

and the quintic polynomial  are plotted below, along with

are plotted below, along with

, all for

, all for  . It can be seen that these are both very good approximations for

. It can be seen that these are both very good approximations for

, say, but not so good near

, say, but not so good near  . The quintic

. The quintic  is much better than the

cubic

is much better than the

cubic  in these outer regions, as might be expected, but can we do better than

in these outer regions, as might be expected, but can we do better than  with some

other cubic polynomial function?

with some

other cubic polynomial function?

When  , for example, the error in using the cubic is

, for example, the error in using the cubic is  . We will

construct a cubic polynomial function

. We will

construct a cubic polynomial function  whose values differ from those of

whose values differ from those of  by less than

0.001 for

by less than

0.001 for  . The curve

. The curve  has been included in the graph below for

has been included in the graph below for  ,

and it is clear from the graph that this curve is closer to that of

,

and it is clear from the graph that this curve is closer to that of  than

than  is, even

near

is, even

near  .

.

We will use Chebyshev polynomials to construct  . These are used extensively in approximation problems, as we

are doing here. They are the functions

. These are used extensively in approximation problems, as we

are doing here. They are the functions  given by

given by

for integer  (or you can write

(or you can write  ). By properties of the cosine, they

all have domain

). By properties of the cosine, they

all have domain ![[-1,1]\,](/images/math/5/8/1/581a26dec23e9f937a02a278e20fc9c3.png) and their range is also in

and their range is also in ![[-1,1]\,](/images/math/5/8/1/581a26dec23e9f937a02a278e20fc9c3.png) . Putting

. Putting  and

and

gives

gives

but it is not immediately apparent that the  are indeed polynomials for

are indeed polynomials for  . To see that this is

the case, recall that

. To see that this is

the case, recall that

from which, after adding these,

Therefore,

Now put  and obtain

and obtain

and so on, clearly obtaining a polynomial each time. As polynomials, we no longer need to think of their domains as restricted to

![[-1,1]\,](/images/math/5/8/1/581a26dec23e9f937a02a278e20fc9c3.png) .

.

Returning to our problem of approximating  for

for  with error less than 0.001, we notice

first that the quintic

with error less than 0.001, we notice

first that the quintic  has that property. In fact,

has that property. In fact,

and the theory of alternating infinite series shows that  throughout our interval, as

certainly seems reasonable from the figure. We next express

throughout our interval, as

certainly seems reasonable from the figure. We next express  in terms of Chebyshev polynomials. Using (5)

and (6), we have

in terms of Chebyshev polynomials. Using (5)

and (6), we have

so

Since  when

when  , omitting the term

, omitting the term  will admit a further

error of at most

will admit a further

error of at most  which, using (7), gives a total error less than 0.0008, still within our bound

of 0.001. Now,

which, using (7), gives a total error less than 0.0008, still within our bound

of 0.001. Now,

and the cubic function we end with is the function we called  .

.

We have thus shown, partly through a graphical justification, that values of the cubic function  , where

, where

are closer to values of  , for

, for  , than are values of the cubic function

, than are values of the cubic function

, which is obtained from the power series representation of

, which is obtained from the power series representation of  .

.

Conclusion: The Point of the Story

The effectiveness of Chebyshev polynomials for our purpose here arises in part from a property of the cosine function. It implies that for all integers  and for

and for  , we have

, we have  . Pafnuty Lvovich Chebyshev, whose surname is often given alternatively as Tchebycheff, was Russian; he introduced these polynomials in a paper in 1854. They are denoted by

. Pafnuty Lvovich Chebyshev, whose surname is often given alternatively as Tchebycheff, was Russian; he introduced these polynomials in a paper in 1854. They are denoted by  because of Tchebycheff.

because of Tchebycheff.

The procedure outlined above is known as economization of power series and is studied in the branch of mathematics known as numerical analysis.

Economization is not always necessary for evaluating the sine function. Because  is approximately

is approximately  when

when  is small, this is often good enough! See Chuck Allison, Machine Computation of the Sine Function, for more on this. We mentioned at the beginning that the Cordic algorithm is often better still, but for evaluating other functions on a calculator, particularly

is small, this is often good enough! See Chuck Allison, Machine Computation of the Sine Function, for more on this. We mentioned at the beginning that the Cordic algorithm is often better still, but for evaluating other functions on a calculator, particularly  , which has the slowly converging power series expansion found in (3), economization is considered to be essential.

, which has the slowly converging power series expansion found in (3), economization is considered to be essential.

Perhaps the point of the story is that the obvious can very often be improved upon.